[ad_1]

The Native Americans who have lived here for thousands of years say that a giant serpent once menaced them from the high-desert hills that surround Upper Klamath Lake, a marshy expanse of water north of the Oregon-California border.

It slithered down from remote crags to hunt people until the creator, G’mok’am’c, butchered it with an obsidian blade. He cast the pieces into the lake, where they became c’waam, a variety of suckerfish that can live up to 50 years and has become the ecological and religious heart for the tribes that call this place home. G’mok’am’c told the people that their fate was tied to the fish — if it perishes, so will they.

For decades, an agonizing war over a scarce resource — water — has divided indigenous people and the descendants of settlers of this region, which like much of the American West, is now plagued by drought.

Family farmers often describe the conflict as one that pits them against federal bureaucrats who protect the suckerfish, imperiled as the lake grows more inhospitable. That portrayal, say members of the tribes, dismisses a tougher truth.

Just under the surface, they say, the real fight is about race, equity and generational trauma to a people whose history includes slaughter, forced removal of children, federal termination of their tribal status and loss of land — but not loss of the shared culture they hold sacred.

“Our water crisis still exists in part due to racism, and racism toward the tribes still exists in part due to our water crisis,” said Joey Gentry, a tribal activist who moved back to the area three years ago after living in Portland.

“I fear that I’ve been vocal, and somebody could be angry and take it out on me,” she said. “I personally fear certain parts of town amongst certain types of people.”

This year, the conflict is more intense than before, with a faction of far-right activists threatening to use force to take control of the irrigation gates that determine how much water stays in the lake, and how much goes to farm fields. The lake, about a hundred miles around, received little snow melt and is shallow enough to walk across in places. Later this summer, as in past years, it is likely to be too hot and toxic for the c’waam and another variety of federally protected suckerfish, the koptu, to spawn and survive.

To ward off extinction, federal regulators have cut off every drop that normally flows from the lake to fields — but are still providing huge pulses of water to help another protected variety of fish, a salmon, down river. Native Americans don’t control the water but hold senior legal rights to it through a treaty that guarantees them the ability to hunt, gather and fish on the land of their ancestors. They’ve long argued that poor lake conditions are decimating the fish and their government-given rights.

With no irrigation water, farms are dying along with the near-ghost towns with names like Keno, Tulelake and Dairy, that surround them. Young people who once may have taken over family concerns are now looking elsewhere as their parents leave dry dirt unplanted. Those who inherited farms homesteaded generations ago are furious, and frightened.

On all sides of the debate this much is clear: There is no compromise to be found. This season, there will be winners and losers. Since the last water shut off two decades ago, global warming has worsened conditions, bringing the region to a breaking point — of climate, belonging and patience.

“There is just too many people and the water is not available for everybody,” said Don Gentry, chairman of the Klamath Tribes and Joey’s older brother. “It’s just not there.”

“Our water crisis still exists in part due to racism, and racism toward the Tribes still exists in part due to our water crisis.”

Joey Gentry, a tribal activist

Klamath tribal member and activist Joey Gentry surrounded by signs used in a recent demonstration in Klamath Falls.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Tribal leaders long have discouraged calling out discrimination, in daily life and in water policy, for fear of making the situation worse, they said. They say they’ve faced increasing acrimony as they’ve successfully defended their water rights in federal courts.

“We’ve kind of kept to ourselves for a lot of years. That’s probably been the safest thing to do,” Don Gentry said.

When farmers last lost their water during the 2001 drought, the situation grew so ugly that the elder Gentry felt uncomfortable visiting Klamath Falls from Chiloquin, a rural area about 10 miles north, where many tribespeople live. A person spat upon one of the tribal leaders. When tribal members went into restaurants, they sometimes were not served water, he said.

A bumper sticker with a c’waam being urinated on appeared on vehicles, with the tag line, “Here’s your water, sucker” and a group of men drove through Chiloquin firing weapons. For years, BB holes pocked the sign at the elementary school.

Recently, Gentry has seen signs of that era returning. A few weeks ago, a nonnative man with a gun pulled up to his grandson’s car, he said, threatening him.

“We are so far out west in the Klamath Basin, it’s so back in the old times … like nothing ever changes,” said Charlie Wright, a tribe member and receptionist at a health center.

For younger tribes members, the energy of Black Lives Matter has helped embolden them and led to a shift in tribal policy. While it once was taboo to go public with racial grievances, Wright this spring led one of the largest public actions in support of her people in decades — her first foray into activism.

Wright, who has three young sons, says the “ripple effect” of the civil rights movement sparked by George Floyd’s death has reached the Klamath.

“I’m not going to put up with this for my kids,” she said. “I don’t want them to have to put up with this. It’s bull crap.”

Both Wright and Joey Gentry are cautious to note they are expressing personal opinions and not speaking for the tribes — which is forbidden under tribal law for anyone except leaders.

Tribal leaders are aware of the internal frustration and say they support what younger members are doing. Tribal leaders also understand what it means to have more support from Washington than they did under the previous administration.

President Biden appointed the first Native American secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, earning praise from California tribes. She recently supported dam removal in the Klamath region, saying it would “deliver environmental justice” and “fulfill the federal government’s trust and treaty responsibilities”

Klamath tribal member and activist Charlie Wright.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland arrives to testify before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on June 16.

(Caroline Brehman/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Imag)

Highway 97 separates farmland from the Upper Klamath Lake in Oregon. The federal government has cut off annual water flows to family farms.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Extreme anger

The Upper Klamath Lake feeds a vast web of federally built canals that sustain fields of alfalfa, onions, mint, potatoes and more on land the U.S. government provided to military veterans beginning after World War I. It’s an area known as the Klamath Project, or just “the project” to locals, made up mostly of neat rectangular plots meant to provide sustenance for families of five on drained lakebeds.

Each year, at the southern end of the lake, a crane hoists six massive concrete gates weighing about 5,600 pounds each into the air, allowing water to gush through the complicated irrigation system. The water ultimately passes through wildlife refuges — providing sanctuary to water fowl such as pelicans and egrets that once thrived in the marshes — before returning what remains to the Klamath River many miles downstream. Courts have deemed that irrigators have a usufructuary right — a type of property right that allows use of something in the public domain — to the top six feet of water in the lake.

The project is a feat of engineering but also an illustration of the federal government promising more than nature can deliver. In past years — those wetter than the last two — the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation has forged deals that please no one but kept a fragile stability for the people and entities with rights to the water.

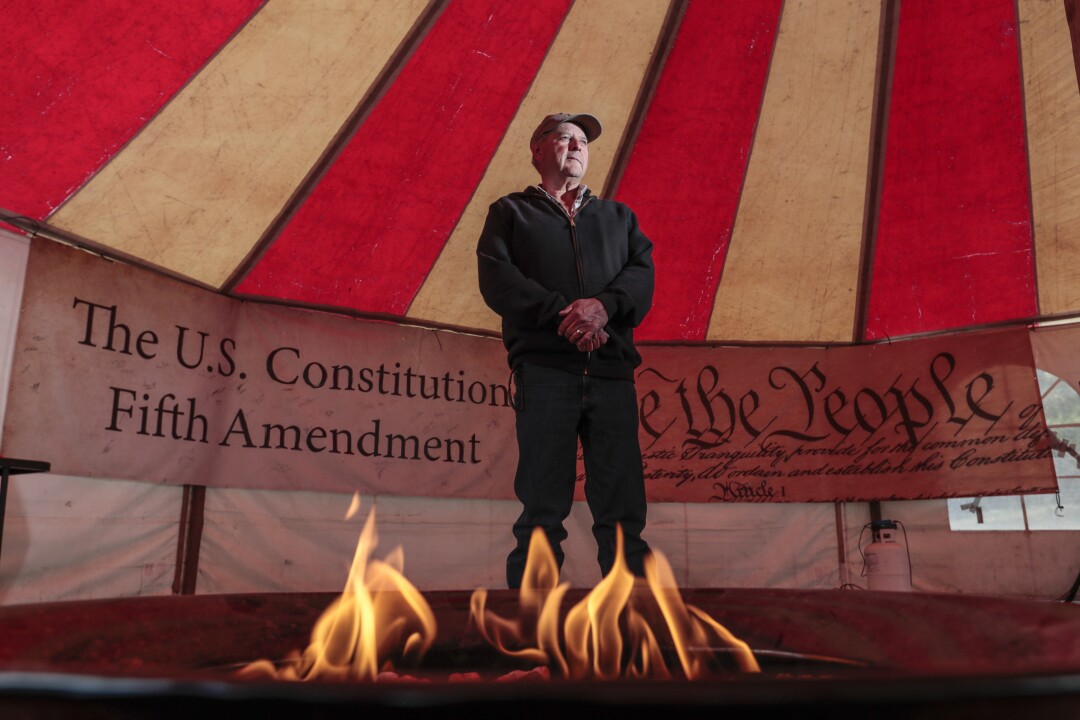

Now, a red-striped circus tent sits ominously just feet from the concrete gates, set up by a far-right fringe aligned with anti-government activist Ammon Bundy, known for his conflicts with federal authorities, including the armed 2016 occupation of the Malheuer National Wildlife Refuge. Bundy has long preached that the federal government lacks the right to own or regulate public lands, a message that resonates with farmers who argue they were sold binding state water rights when they purchased their farms.

Many Native Americans see Bundy and his crowd as a threat. When Joey Gentry saw the tent go up, she remembers thinking it was the “end of all possible solutions,” she said.

“You start bringing in white supremacy, militia, anti-government, extremist groups, there goes any hope for solutions,” she said.

Dan Nielsen inside a circus tent he set up on land adjacent to a canal gate that controls water flowing into the irrigation canals of the federal Klamath Water Project. He is threatening to remove the steel plates that block the water’s flow.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

One protest organizer, Dan Nielsen, is living in an RV at the site. Nielsen is a small-time farmer and truck broker who has little hope of getting water from the canals this year, but says he does have access to a crane to remove the gates if need be. The water, he says, is his by right and law — Nielsen was among those who set up a similar protest in 2001 dubbed “the bucket brigade” that drew about 18,000 participants.

In July of that year, activists broke into the head gates and turned the water on. They voluntarily left, under the watchful eye of federal marshals, after the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in New York in September.

If force is required to take water again this year, said Nielsen, he is ready. He and another protester purchased the land they are occupying, giving them private property rights to be there.

“They illegally seized our water without due process of law, no court order, no nothing,” Nielsen said standing inside the tent, lined with banners extolling the 5th Amendment of the Constitution. “The government promised [the tribes] water that’s not theirs. The government doesn’t have any water rights. … That’s just the federal government bullying the frickin’ people.”

On his cell phone, Nielsen has text messages between himself and Bundy, including the militant’s promise to support the farmers.

Dread of Bundy’s intervention has been a powerful bargaining chip with federal authorities.

“They fear Bundy,” Nielsen said.

Last fall, Nielsen visited Bundy in Idaho and joined him when he stormed the state Capitol to protest coronavirus restrictions, Nielsen said. Afterwards, he spent the night at Bundy’s house talking about the Klamath situation. In the morning, Bundy made him pork chops and eggs for breakfast while Bundy’s wife taught Scripture to their children, he said. They talked about the need to educate people on Bundy’s ideas. Most people, said Nielsen, are “like sheep. … They don’t even know what’s going on. I mean, they are headed down the slaughter chute right now, getting ready to get their heads chopped off.”

The visit left Nielsen convinced he had an ally in the renegade cowboy.

“He will stand up,” said Nielsen.

Tulelake Irrigation District Manager Brad Kirby is known as “the bringer of doom” to constituents who often hear from him that water allocations are shrinking fast.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Pragmatic middle

Between the tribes and the people in the tent are the majority of Klamath Project farmers, anxious not just for this season, but their ability to hang on past it.

“It’s scary,” said Tulelake Irrigation District Manager Brad Kirby, who is known as the “bringer of doom” for often informing constituents just how little water will flow their way. “If there’s no willingness — and a reasonable approach from the tribes in particular, to work with us right now — I don’t know what happens to my own town.”

Once considered the most thriving of local farm towns, with a bakery along the main drag and Jock’s Supermarket on the corner, Tulelake feels abandoned. The family that owned Jock’s sold out, and it’s mostly a liquor store now, shelves stocked with Hamburger Helper and beer. Main Street is nearly empty of stores. The population has dropped to about 800 people.

Farmer Paul Crawford picks a healthy wheat stock from a friend’s farm to show what a properly irrigated plant looks like. He has had to fallow some of his fields to conserve dwindling water rations.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Crawford prepares to run his hay bail retriever.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Paul Crawford is one of the few younger farmers to try to make a go of it. In 2011, he returned from an Army stint in Afghanistan and bought land from his best friend’s dad — he now owns about 585 acres that he works with his wife and kids, Heston, 9, and Paisley, 7.

Recently, after a good year in 2016, he and his wife bought a white farmhouse with 40 acres of alfalfa out back and goats on the side. A new barn is being framed out, but he’s not certain he’ll still own the place by the time it’s done. Only about 40% of his land is planted this year.

Like many farmers, he believes that federal fish science is flawed and unnecessarily holding back lake flows that should be used for fields. For years, despite keeping water in the lake, the sucker fish have not recovered. Neither have the downstream salmon. He thinks it’s time to try a different approach.

“I feel like I’m not fighting a fish. I feel like I’m not fighting the tribe,” he said. “I feel like I’m fighting bad science.”

Crawford says he doesn’t want violence and doesn’t want Bundy in town, but recognizes the anger that led Nielsen to erect the tent. “Everyone’s kind of backed into their own corner,” he said.

Even moderates — those unwilling to take the law into their own hands — are frustrated by the tribes’ hardline stance, and some accuse them of “playing the race card” in a bid for more political power.

“The problem is the attitudes have changed and it’s not all about fish anymore,” said Scott Seus, a third-generation farmer. “It’s about retribution, it’s about colonialism, it’s about a whole bunch of things that are buzzwords right now in our society.”

Council member Clayton Dumont, left, and tribal Chairman Don Gentry stand next to the Sprague River, which flows to Upper Klamath Lake.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Dumont, the tribal leader, said he understands the farmers are hurting and appreciates irrigation leaders who’ve tried to distance themselves from Bundy. But his sympathy goes only so far.

A few miles from the tribal headquarters, Dumont recounts some history of the tribes, including Native Americans hanged after waging warfare against white settlers to protest removal from their lands. Their leader, Kintpuash, was decapitated and his head sent to a medical museum.

The Klamath Tribes were also involuntarily subjected to the Termination Act of 1954, which eliminated their recognition as a tribe and turned their reservation over to the federal government, much of it becoming the Fremont-Winema National Forest.

Dumont’s grandparents, plagued by alcoholism, sent his father to a brutal boarding school, he said, as the U.S. government attempted to pressure Native Americans into Western culture. The Tribes, he said, are working to overcome “generational disaster” that can’t be separated from the fate of the lake or the sucker fish.

“Our memories are really long. You know, they talk about being fourth-generation farmers. I like to say we have gossip that’s older than that,” Dumont said. While he doesn’t blame current farmers for past wrongs against Native Americans, he said the current fight is a continuation of “this struggle over that privilege that they don’t believe they have.”

“I don’t think it’s unreasonable to want to protect our home,” he said. “I like to say every living thing protects its home.”

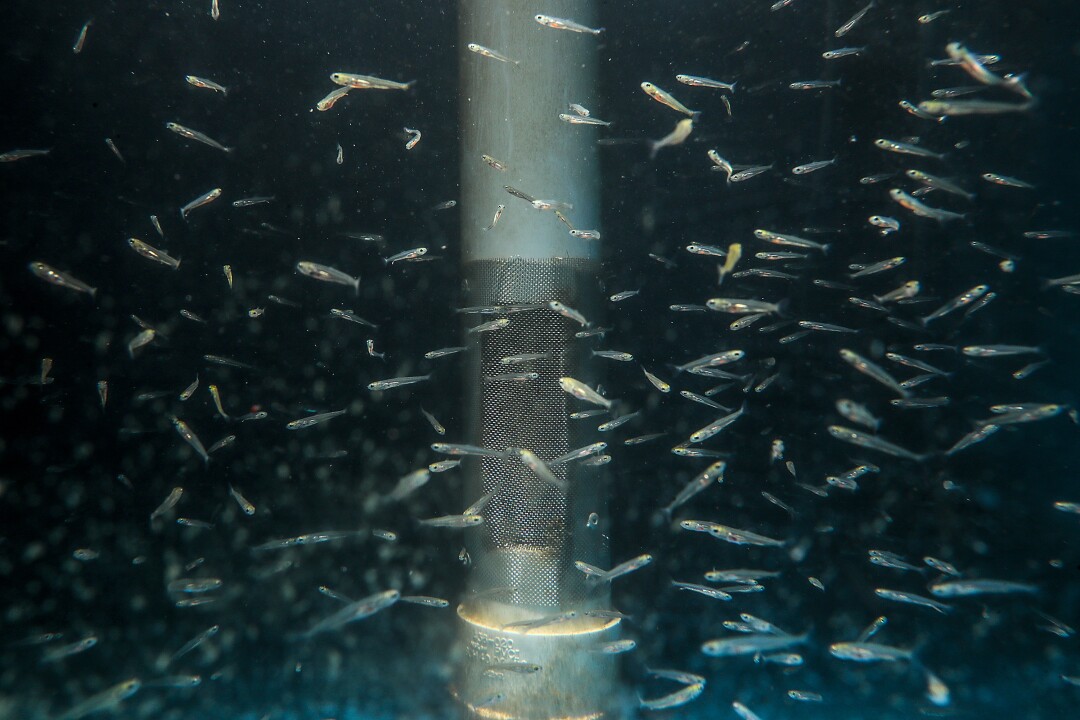

The Gone Fishing complex is home to thousands of endangered sucker fish that will eventually be released back to the Upper Klamath Lake.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

window.fbAsyncInit = function()

FB.init(

appId : ‘134435029966155’,

xfbml : true,

version : ‘v2.9’

);

;

(function(d, s, id)

var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0];

if (d.getElementById(id)) return;

js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id;

js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js”;

fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);

(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’));

[ad_2]

Source link